If you’re looking for rich, historical fiction with captivating flourishes of magic and meta-fiction, look no further than the works of Dan Simmons. I’m finally catching up with Mr. Simmons’ 2015 novel The Fifth Heart. Much like his earlier novels Drood and Black Hills, The Fifth Heart combines authors and fictional characters with historical events and defies genre classification.

If you’re looking for rich, historical fiction with captivating flourishes of magic and meta-fiction, look no further than the works of Dan Simmons. I’m finally catching up with Mr. Simmons’ 2015 novel The Fifth Heart. Much like his earlier novels Drood and Black Hills, The Fifth Heart combines authors and fictional characters with historical events and defies genre classification.

“Am I a fictional character?’ ponders the great detective Sherlock Holmes, as he partners up with the writer Henry James to solve the mystery of Clover Adams’ death. Clover Adams, the photographer and member of the Five Hearts, a group of five close friends, was presumed to have committed suicide – but the mysterious typed cards that arrive in the other members mail on the anniversary of her death declare her death to be murder.

Holmes and James cross the Atlantic to investigate her death, retracing the events of 1885 that led to Clover’s presumed suicide. Along the way, they meet Sam Clemens, and travel to his home in Connecticut. Henry Adams and the others member of the Five of Hearts, Clara and John Hay, and Clarence King host Holmes and James in Washington D.C.

The Adams Memorial in Rock Creek Cemetary

Simmons packs this novel with adventure and excitement that match any of the Holmes exploits written by Conan Doyle – and perhaps exceed them in outlandishness. There’s a moonlight scene in Rock Creek Cemetery at Clover’s memorial that has the reader squinting to see more of the dimly lit action. And picture the portly Henry James eavesdropping at a meeting of anarchists!

Simmons is also not afraid to reference earlier works of his own, calling upon the character of Paha Sapa from Black Hills to have a moment with Holmes.

The story culminates with Holmes and James racing to intercept a murderous sniper at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

The Fifth Heart combines all the best of Holmes adventures and historical fiction. However, it is a novel that the reader will enjoy more fully with some background knowledge – perhaps even insider knowledge would be a better term – and this can be a turn off to some.

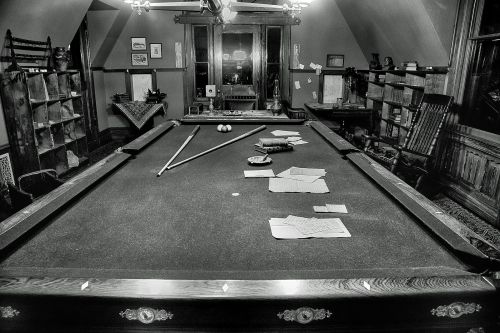

I thoroughly enjoyed the meta fictional aspect of the novel, as Holmes mused on his own existence, as well as the nods to Holmes’ history and the historical events of the Columbian Exposition. Holmes and James’ trip to Clemens’ home in Hartford, Connecticut was a special treat for me, as I visited the Mark Twain House a few years ago with a dear friend. I could easily visualize the scene in the well appointed, supremely masculine billiards room at the top of the house.

I recommend this book to fans of historical fiction and lovers of Holmesian fiction.

Recommended companion books: Devil in the White City by Erik Larson, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle, and anything by Henry James.

Teenage heroine? Check. Desperate love story? Check. Rural scenes combining cruelty and desperation? Check. Urban/suburban neighborhoods hiding corrupt underbellies? Check.

Teenage heroine? Check. Desperate love story? Check. Rural scenes combining cruelty and desperation? Check. Urban/suburban neighborhoods hiding corrupt underbellies? Check. Fates and Furies by Lauren Groff is almost perfect. This compact novel first masquerades as a domestic drama, but about 50 pages in I realized there were too many layers to label it that.

Fates and Furies by Lauren Groff is almost perfect. This compact novel first masquerades as a domestic drama, but about 50 pages in I realized there were too many layers to label it that.

Contemporary histories have distinct advantages: first hand accounts, plentiful documentation, and photo records. The Day the World Came to Town: 9/11 in Gander, Newfoundland by Jim DeFede has the dubious advantage of being an account of one of the defining moments in American history, and one of the most documented. But contemporary reports also have drawbacks, and I observed a few in this highly readable book.

Contemporary histories have distinct advantages: first hand accounts, plentiful documentation, and photo records. The Day the World Came to Town: 9/11 in Gander, Newfoundland by Jim DeFede has the dubious advantage of being an account of one of the defining moments in American history, and one of the most documented. But contemporary reports also have drawbacks, and I observed a few in this highly readable book. What started out as a disappointing retelling of a Beauty and the Beast legend morphed into something richer and more complicated.

What started out as a disappointing retelling of a Beauty and the Beast legend morphed into something richer and more complicated.

Tomlinson Hill by Chris Tomlinson recounts the history of the Tomlinson families of Tomlinson Hill, Texas – one a privileged white slave holding family, and the other family, the slaves that took the Tomlinson name. Tomlinson begins the book with the migration of the white Tomlinsons from Alabama to Falls County, Texas with their slaves walking the distance as the masters rode.

Tomlinson Hill by Chris Tomlinson recounts the history of the Tomlinson families of Tomlinson Hill, Texas – one a privileged white slave holding family, and the other family, the slaves that took the Tomlinson name. Tomlinson begins the book with the migration of the white Tomlinsons from Alabama to Falls County, Texas with their slaves walking the distance as the masters rode.